It was roughly one year ago that I actually paid attention to a Head Vase. Before, I saw them here and there and in old books and tv shows but had no real interest at that time. So, I was out product sourcing a year ago for some auctions I was going to post up for the weekend when I came across a “Norleans” lady Head Vase with the long black eyelashes, a gorgeous head of blonde hair and siren red lips. That Norleans head vase was a small 4 1/2 inch head vase and looked so amazing that I went into the booth she was in and took her off the shelf to get a better look. I took her home that afternoon and she was sold before the week was over! Now, I wish I would have kept her as I would love to start my own collection as I am truly fascinated by the beauty and glamour of vintage Head Vases.

For those that are advanced collectors and for those that are just getting started on their collections, the below is some great information on Head Vases that I hope you enjoy reading.

Head Vase History

With World War II a memory, America prospered in the late 1940s and 50s. Japan was no longer the enemy; instead, with its lower labor costs as well as the favorable dollar/yen exchange rate, the island nation increasingly became the source of many low-cost imports to the United States. Small ceramics were among the most popular—including head vases, which today have become extremely collectible.

Back then, few would have anticipated the current popularity of this commodity which, for decades, florists used as inexpensive enhancements for their bouquets. Indeed, what today we usually refer to as “ceramic planters” or “head vases,” was often then generically called “florist ware.” Neighborhood “five and dimes” were popular sources for the more affordable pieces.

But Japan wasn’t the only country to produce such items; America made its share as well. Stateside companies such as Betty Lou Nichols Ceramics, Ceramic Arts Studio, Florence Ceramics, Josef Originals, Roseville, Royal Copley, Royal Haeger, Shawnee Pottery, Stanford Pottery, and Weller were prolific producers. But as U.S. labor costs increased in the 50s, so did competition, making the production of such novelty items less and less profitable. Copyright, especially abroad, was not enforced; in many cases, firms would mimic each other’s designs, with only a change in paint color, size, or other subtle detail to differentiate the manufacturers’ products. For these reasons, the majority of U.S.-made head vases found today were produced prior to 1950, while Japanese imports continued strongly into the 60s.

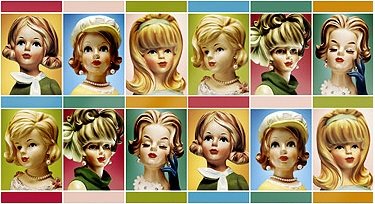

Head vases were made in a variety of designs. But it was the elegant, fashion-model look that quickly became among the most popular. Flourishes such as faux-pearl necklaces and earrings, hair bows, eyelashes, and applied textiles became the norm. Glamorous movie stars and beautifully coiffed fashion models inspired many of the designs both here and abroad. One novel approach, which quickly became commonplace, was the addition of a well-manicured hand. Positioned so as to be stroking the face, this gave a touch of feminine elegance to the piece. Another common embellishment was the attachment of separate items to the planters. Examples include buckets hung with string around a laborer’s neck or a textile or ceramic parasol held by a sweet little girl.

The market for such ceramic pieces peaked in the mid-60s. By this time, designs had become simpler, often smaller, in order to reduce costs and increase profitability. Whereas many early head vases topped 8″ in height, newer ones were often only 3-4″ tall.

Today, head vases of all types have become very collectible. Those which originally sold for only a couple dollars each now command many times that. Pieces depicting well-known personalities, such as the popular Jacqueline Kennedy by Inarco or the Disney character series by Enesco, are often most highly prized. While many head vases can be identified by their hallmarks (which may be part of the mould itself, painted directly onto the item, or applied as a sticker), others have no identifying marks whatsoever. Often only the style of the subject’s hair or clothing attest to the item’s age, if not its manufacturer. Because they could not predict today’s collectibility of ceramic head vases, manufacturers typically did not save their records; most historical documentation therefore has been lost forever.

Manufacturers

Brinn’s China-Glassware Co.

Founded by Samuel I. Brinn in the early 50’s, the Pittsburgh-based company stayed under the management of the Brinn family. In its beginnings, Brinn’s was a wholesaler of art ware, dinnerware, figures, garden pottery, jardinières, premiums, teapots, glassware, ovenware, novelties and various ceramic and glass accessories. By 1959, the company distributed ceramic and brass imports from Japan and England. Two decades later, under the operation of president Charles Brinn and vice president David M. Brinn, the company was listed as ian importer of ceramic figurines, animals, novelties, dinnerware, stainless steel, and dolls.

Ceramic Arts Studio

In 1941, Lawrence Rabbit and Reuben Sand launched Ceramic Arts Studio as a manufacturer of china figures, art ware, and florists’ ware. The company, which used the clays of its native Madison, Wisconsin, commissioned celebrated designer Betty Harrington to decorate its large line of elegant animals and figurines. Ceramic Arts Studio remained a leading manufacturer until Sand decided to sell the business in 1955, and the company moved to Japan. In the Pacific island nation, Ceramic Arts Studio reintroduced many of the manufacturer’s original items. While such copies have caused confusion over the actual origin of some Ceramic Arts Studio pieces, it is important to remember that the American-made versions feature a Ceramic Arts Studio Madison Wisconsin © and usually carry the figurine name as well.

Enesco Corporation

One of the largest head vase manufacturers in the world, Enesco was founded in 1959 by Eugene Freedman. Originally operating a small plastics and figurine company in Milwaukee, Freedman soon joined a Chicago-based import company, which had spun off of a prominent wholesale merchandising operation, N. Shure Co., the name of which morphed into N.S. Co.—and ultimately, Enesco. The company began by marketing Southeast Asian giftware out of its modest Elk Grove, IL facilities; by the 80s, Enesco had expanded its presence throughout the U.S., and into Canada, Puerto Rico, Hong Kong, and Europe. Most designs of Enesco head vases were made by Japanese pottery makers and are marked exclusively with paper labels. Continue Reading.